RASHID MOGHUL, at seventeen, had only two weaknesses. First, that he fell obsessively in love with a rich Kashmiri Zamindar’s daughter and the second, that he was a compulsive liar. The former was a consequence of growing up together. They were from the same village in the Lolab valley. Known locally as the Wadi-e-Lolab, poets often referred to it as the land of love and beauty. Formed by the flow of the Lahaul river from east to west and at a height of 5500 feet, the Lolab was a paradise prompting Iqbal to poetic expression; ‘your springs and lakes with water pulsating and quivering like quicksilver’. It was what the Americans call a high school romance, except that it was one sided.

Typical of the caste hierarchy that existed in Kashmir, the Gujjars occupied the higher reaches of any village, while the affluent Kashmiris, the more fertile and accessible parts. Rashid’s house was further up the mountain on the fringes of the forest, with its own piece of attached land. A few walnut and apple trees with the meagre produce from the land was the only subsistence for the family. From school to shopping the path from Rashid’s house led past Zaira’s house. Proximity for years heightened passions in him to possess her, turning desire to love and eventually, into an all-consuming obsession. Being a poor Gujjar boy, the impossibility of a future matrimonial alliance between the two only enflamed the desire to possess. Rashid’s second weakness was an aftermath of a cruel childhood – an unemployed sick father, whose frustrations of life were expressed in violence on the poor boy. Necessity for survival led to lying, turning it into a habit in the years to come.

Physically, he was neither tall, nor short, with an intelligent, sensitive face. He had a straight nose and eyes which were large and melancholy. They were the windows, exuding a sad present and a painful past, for in them, you read like an open book, his character and thoughts. Petulant lips, with just an insinuation of a moustache and a beard in the offing enhanced his adolescent appearance. By the time he left school to work his father’s meagre land (for he was the only child), ominous clouds had been steadily gathering over the valley of Kashmir. A cry of azadi and jehad was a perennial echo with an unheeded message of the impending hell to follow. Very soon in hundreds, young men in the valley and especially from the Lolab being a border district, crossed the border, into Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK), to return flaunting the magic wand – the Kalashnikov rifle. Calling themselves the Mujahideen, they spoke of the holy war, like a game to be played. Kashmir was to be liberated and to die fighting for the cause got you shadat and a place in Jannat.

Rashid, however, at the insistence of his mother, kept himself aloof from the virulent seditious wave sweeping his generation. Harsh domestic responsibilities kept him engaged. A father, who was gradually losing out to cancer and a frail sick mother, whose entire time went in nursing her husband, necessitated the chores of existence fall on his young shoulders. Bulk of the earnings from the meagre land and the sale of fruits was swallowed up in treating his father. The strain was telling on his mother and he could see how rapidly she was aging. She often remarked that she needed a woman at home to help her out with the domestic responsibilities. In fact, she had already broached the subject of a wife for Rashid to her elder brother, who had a daughter, a couple of years younger than Rashid. But Rashid had made up his mind on the subject long back. It would be Zaira, the Kashmiri girl, or no other woman for the rest of his life.

Since leaving school, he realised, even Zaira had become a rare sight. In the evenings he would often go past her house, to catch a glimpse of her at the window or carrying water from the stream which came down from the Khobalmargi top.

“Asalam Walikhom,” he would call out and she would blush coyly, returning the greeting. And that is where the conversation would end.

For hours at night Rashid would restlessly toss and turn seeking answers to a hundred unsolved questions. Did she love him? The way she smiled…maybe she did. But then the other day she had been rather cold, probably she had found another man; an enigma indeed. Until, like always in such flights of fantasy, he would get stuck on the most crucial point – even if she did care for him, how would that change his situation? She was a rich Kashmiri girl and he, a poor Gujjar and in all probability, her parents may have already found a man for her. On that note, he would tire himself to sleep.

Life for Rashid Mogul continued at its own lethargic pace. From days to weeks to months, nothing changed to enliven his mundane existence. The silver lining, which he prayed for, remained as nebulous as it had been for the past seventeen years. Then in the beginning of ninety-four, a maelstrom of events swept past him and like an insignificant twig in a typhoon, the raging tide of destiny carried him with it at a furious pace – a pace much beyond his powers could control and he followed in a daze. The Arabs call it Maktub; it is written.

His father died one night and went the way he had lived – cursing the world for his miseries. Massive flakes of snow danced earthwards and a howling wind cut through to the bones when his jenazah went out in the morning. A contemptuous sneer still lingered on the old man’s face. As if in death he had finally won the last round. Strangely, Rashid felt no pain at the loss. He only wondered if he too would go to his maker like his father, a bitter man to the end.

The harsh Lolab winter loosened its grip and the weather cleared. A few weeks later while shopping in Kupwara town, he met Zaira. She seemed to be in a responsive mood and Rashid, taking advantage, persuaded her to have a cup of tea and some kababs. Then without giving her time to protest, he pulled her into the nearest studio. With a massive poster of the Swiss mountains in the background they got themselves photographed, like a brother and sister would in a family photograph.

A few days later he collected the snap. All the way back to his village, he kept admiring it. The results pleased him. He was laughing while she, resplendent in a red firan, seemed stiff and nervous. But how beautiful she was, he thought. He had never been so happy in his entire life. Things seemed to be finally looking up. He muttered a few words of thanks to Allah and in an exuberant mood, warbling an old Kashmiri song, trudged home through the sludge created by the melting snow.

He passed Zaira’s house and a strong impulse to show her the snap suppressed his further progress. Mustering courage he ascended the stairs to her house. It was the most inappropriate moment for him to have done so, for a heated family discussion was in progress. Zaira’s elder brother had just returned from POK, flaunting a gun and openly declaring his intention to join the militant group Hizbul-Mujahideen. The father was dead against it, while the uncles supported the young man’s decision to join the holy war. Tempers were running high and Rashid’s presence offered a perfect target to vent their emotions.

One look at the silent assembly and he regretted his actions. Rashid suddenly felt very small and scared amidst the hostile family, as they glowered at him. He stood there nervously, like a naughty child waiting to be admonished by the entire school staff.

‘It’s Jamaluddin’s son,” said the mother.

“Well what does he want here?” growled the father.

“I have seen him, hanging around here often,” added the mother.

“Let’s see what are you holding in your hand?” asked one of the uncles, snatching the snap from Rashid’s hand.

As he stared at the photograph, his face turned red and a vein started to twitch on his neck. “Yah Allah!” He erupted, “the Gujjar pup has eyes on our daughter.”

He passed the snap to the father whose face became ominous and then without warning, he raised his firan and flung the hot contents of his kangri onto the poor boy. Most of it missed but some of the glowing coal embers found their way through the collar of his jacket, scorching his skin instantaneously. He screamed to a macabre dance, as he tried to dislodge the pieces stuck in the folds of his jacket and then turning in pain and humiliation, he ran back home crying, as bawdy remarks about his ancestry followed him from behind.

The entire week, he stayed indoors, nursing his wounds and wallowing in self-pity. Then piqued and seething in anger at the insult, and realising that impotency and poverty wouldn’t get him anywhere, he started packing his meagre belongings.

“Where are you off to?” his mother asked, alarmed.

“I have to go before Zaira’s brother Shafi turns up. He’s a mujahid and its perilous to expose myself here.”

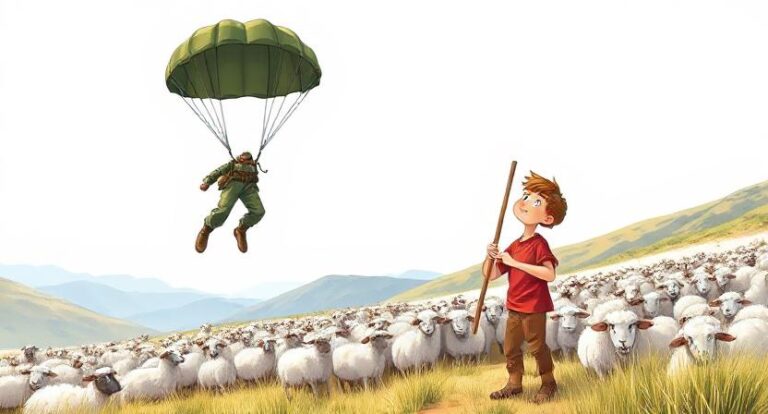

He contacted the local Al-Barq Launch Commander at Dobain and with a group of twenty boys crossed over to POK. The authorities at the first Pakistani post Lohsar -1 checked his antecedents, asked a few questions and immediately weighed him up as a below average guerrilla material. A civilian truck took them further into the hinterland to a training camp close to Muzaffarabad. The trainers wasted little time on him. Rashid was taught weapon handling, firing and arming him with an AK- 47, four magazines and a couple of grenades, in a month’s time they pushed him back across the border in to India. The logic was simple. Another man with a weapon was another little problem for the Indians.

He came back and joined Nadir’s group operating in the North Lolab. It was an all Gujjar party and generally more benign when it came to operations against the security forces, in comparison to the more hostile and belligerent groups like the Harkat or the Lashkar. For a year or so he moved around with the team evading the army and generally living off the largess of the villagers. To justify their existence so as to insure the Paki’s didn’t turn off the financial tap, they often resorted to engaging an army post or patrol from a safe distance. It seemed the basic aim of the party Al Burq was to protect the interest of the Gujjars and maintain a power balance with the Kashmir’s in general. For power often flows from the barrel of a gun. And the Gujjar who always had a more pecuniary interest than ideological preferred to sit on the fence and watch, which side would finally dominate the jehadi landscape before taking a side.

In any insurgency there is a swell and ebb in its tide. So by the end of ninety-five the tide had changed. The Army was omnipresent. Most of the old timers in the game had been shot. As the Army authorities put it “the sting was crushed but the scorpion remained.” An Infantry Company along with a troop from the Special Forces had moved in to the villages of Varnau and Kuligam for Counter Insurgency operations. Aggressive patrolling and ambushes had annihilated quite a few local mujahids and the remaining few were relegated to their jungle hideouts in the mountains. If you were a militant, movement had become fraught with grave danger. For the devils who wore the maroon berets and were inhabiting the same the valley had no regard for the caliber of the opposition, inclement weather or the rugged forested terrain.

Militancy was no more an enchanting prospect it had been in the past and delusions of azadi a far cry. Surrender it seemed was the order of the day. A popular course of action, commonly followed by the not so committed local militants was to get a surrender certificate and join one of the ex-militant groups operating in conjunction with the Army. One had all the protection of the army, you still carried your gun, got free rations and had the authority and the backing of the army to sort out personal issues and grievances with your neighbour.

For two months Rashid moved around with Nadir, eluding the Army, on more than a few times by the skin of his teeth. The hard wild living and constant fear of death made him realise the futility of such an existence. Zaira had been married off in his absence and her brother Shafi long dead. Shot on the border, trying to cross back a second time into India. Rashid’s raison d’être for joining militancy were already over. The writing on the wall was clear. The shadow of death hung low over anyone who was against the state. Temperamentally he was never cut out for this kind of a life and physically and mentally it wore him down to a shadow. He ached to go home. The prospect of surrendering which had been just a seed in his mind now clouded his conscious thinking. Rashid now waited for an opportunity. However, unfortunately for him, Nadir knew what was playing on the boy’s mind.

“Well Rashid,” he said one day, “if you want to surrender, do so but the weapon belongs to the Tanzim. Hereafter, I’ll take charge of it. Now go across and offer yourself,” and with a chuckle he snatched the rifle out of Rashid’s hand. “Hope you know,” he continued, “that the Army does not accept surrenders without a weapon.”

Rashid tried to protest, denying any such plans on his part.

“Huzoor,” he pleaded. “What am I to do without a weapon? And then you are constantly there. Where can I possibly run?”

“Really Rashid,” said Nadir gravely, “you ought to do something about those eyes of yours. When you lie, which is quite often for the most trivial things I have noticed it shows in your eyes. You are a suspect and if I catch you jumping the fence, Inshah Allah I’ll kill you.”

After the rebuke from Nadir and the humiliating way in which his weapon had been taken away, the rest of the group started looking down upon him. He was relegated by the leader to do all the menial jobs like cooking or washing when they were in camp. From a Mujahid he had turned into an errand boy. Then one day, opportunity did knock in an unexpected manner like opportunity often does. The group was sitting over a village, waiting for darkness before going down to one of the houses for dinner. Suddenly there was rustling of the bushes and glancing over his shoulder Rashid saw the thick undergrowth a hundred yards behind and a menacing dark figure loomed out of the thick mist rolling down the mountain. His blood turned to ice water. Then shouting “fauj,” he threw caution to the wind and went crashing through the undergrowth.

The lead scout tried picking him off with single shots, then seeing his quarry rapidly disappearing downhill into the gathering dusk; he flicked the lever to automatic.

Rashid briefly heard excited loud voices behind him and immediately the jungle erupted to a hail of lead, as the entire column opened up in the general direction. An hour later, his chest heaving with exertion, clothes torn with deep lacerations on his arms and face, Rashid stumbled through the front door of his house. Hiding the magazine and the couple of grenades in a niche behind the door, he changed his clothes.

His mother walked in and a worried gasp escaped her lips on seeing his condition.

“What have you done? Where are you off to now?” she asked.

“The Army is after me,” he stammered. “They don’t accept surrenders without a weapon. I am clearing out. Remember me in your prayers,” then hugging his mother warmly, he stepped out into the cold. Briefly he turned, casting a look at the house he had grown up in. A single wicker lamp burnt inside, silhouetting the frail figure of his mother at the door forlorn, sick and sobbing gently in her misery. He heard the cows munching peacefully, smelt the apple blossoms in the air and then with an effort he wrenched himself away. A few minutes later he was on the track under the big walnut trees, a lonely figure in the darkness.

For nine months, Rashid made a living, working as a labourer in Srinagar. Time the healer, perished thoughts of fear and death in him and a strong urge to meet his mother, blinded him to the pitfalls that lay ahead. For how was he to know that destiny had already decided the path he would take. Through an old acquaintance, he sent a message to his mother to meet him at the Drugmula bus stop a few miles, short of Kupwara. But the message never reached her. The man promptly went across to the Army post at Kuligam and passed the information to the Major in charge there.

Clutching a bag full of clothes and victuals, that he had brought as a gift for his mother, from the money saved Rashid Mughul waited at the bus stop. But he waited in vain. For at the appointed hour, a taxi drove up. Two men got out. One of the men went to the cigarette shop, while the other asked for directions from the waiting crowd. None noticed as the man at the shop suddenly turned and approached Rashid from behind, and hooked an arm in his. Then expertly running a hand over Rashid, he led him to the waiting taxi. In precisely five minutes the operation was over. A blindfold was put and both the men squeezed him in the middle as the vehicle sped off.

His blindfold was removed and Rashid opened his eyes to find himself in a tent. His hands were tied behind his back and he was left alone to stew in his own morose gloomy thoughts. At least one thing was clear to him that his abductors were the army and not Nadir and his henchmen as he had suspected. They gave him some time. A couple of hours later the tent flap lifted and a tall bearded good looking man walked in and pulled a camp stool, sat on it, while two sinister looking men stood behind him. They were all in civilian clothes. Rashid’s hopes rose because the tall man was wearing a skull cap and looked a Muslim.

“Asalam Walikhom Rashid.” said the man on the stool smiling and in a surprisingly gentle voice.

“Walikum salaam.” he stammered through dry lips.

“We play the tune here kid, you dance,” said the man. “You stop and major grief will come your way. Now where’s the rifle cached?”

“I don’t have a weapon,” replied Rashid.

“Look Rashid,” continued the man patiently, “others have surrendered to us before. We are aware of the pattern. Hiding weapons and taking up jobs in Srinagar. Come, come kid, the weapon is all we want.”

“By the Oath of Allah, if I had one I would have surrendered long back,” replied Rashid.

He never saw the elbow coming. He opened his eyes to find himself on the ground. His jaw hurt terribly and he was scared, very, very scared.

“Look into my eyes Rashid,” the man continued in the same gentle tone. “Tell me when did you go across to POK?”

“Ninety four, Sir.”

“Sure?”

“Maybe ninety five, I can’t remember now.”

“Look up Rasheed you are lying again. What’s your age kid?”

“Eighteen may be nineteen. I don’t exactly know Sir.”

The punch in his stomach took the wind out of him. He coughed, throwing up, whatever he had eaten.

“You filthy scum,” he heard the man agitated now. “Whimpering like a pup! You didn’t behave like this when you were a mujahid, fleecing honest folks at gunpoint and impressing skirts in the village. Is this what they taught you across? To weep like a woman? What kind of bloody men are you? To allow foreigners to sleep with your sisters and wives? You know Rashid there is a saying; There is another man in every man. and you are a prime case of that. Your eyes are deceitful. Don’t worry, we’ll get the other man out of you soon. I know how tough you are my little mujahid swine.”

A kick, the way you would to a street dog, summed up the man’s speech. He turned to the two men behind him.

“Kuldeep,” he said, “look after our mujahid friend, will you, the usual. Pins, water, telephone and let me know when he starts singing.”

With that he stepped out. The man Kuldeep stepped forward now smiling. Extracting a paper pin from his pocket, he rolled Rashid on his stomach. Then grasping his little finger, he inserted the pin just below the nail and gently pushed it in. The pain was excruciating. Tears welled up in his eyes. He gnashed his teeth and bit his lips till blood started to flow. But the pain just kept increasing. And just before he passed out, he heard laughter and an envious voice asking him, “Well Rashid, how many women did you sleep with?”

It was a warm, lazy afternoon. The officers sat around in the sun, drinking beer.

“You know Sir,” said one of the officers addressing the Colonel commanding the battalion, “Lolab is famous for two things, the Lolabi rooster enormous and very colourful, and the beauty of its women.”

“So I have noticed,” said the Colonel “and it’s high time you went on a spot of leave Andy, been talking too much about women lately.” They all laughed.

“Well gentlemen,” said the Colonel knitting his brows, “haven’t called you here to discuss Lolabi women. More important matters are at stake. We haven’t had a kill for over a month. That, you’ll agree, is rather a long break by valley standards. The Brigade Commander is pressuring for results.”

“You know we have been trying, Sir,” said one of the officers.

“I know guys, I know,” said the colonel. “Stroke of bad luck, should hit something soon. By the way Anil,” he said, turning to a tall, bearded, taciturn officer enjoying his beer. “What about this boy you caught? Any good?”

“Negative Sir. We did recover a little ammunition and some grenades from his house. I have worked on him thoroughly. Rather clean. The usual cock and bull story of how he got into militancy. A harmless low grade militant with a noticeable proclivity to lie. But he’s definitely not a dangerous jehadi with any sort of ideology. Just a scared young man who clearly got carried away with the events around him.”

“Adjutant,” said the Colonel turning to another officer. “Have we shown his apprehension, or surrender so far?”

“No Sir.”

“Tell me, do we have any weapons left in the kitty from the last haul?”

“An AK- 47 and some grenades Sir,” replied the Adjutant.

“God’s own gift to us,” said the Colonel with a laugh, as if suddenly relieved of a heavy burden. “Right Anil,” he continued, “this is what you do. Take the boy up with you and tell him to show you the hideouts he stayed in with Nadir. The information is obsolete and nine months old, but if you are lucky, you may run into Nadir and party. Otherwise knock him off on the way back. He’s still a bloody militant in the eyes of the world. Should give us a few days peace and keep the brigade quiet. Do discuss the details Anil when others have left.”

The plan was simple. Climb at night, hit the ridge-line and roll down by first light.

“According to him,” said Anil, “the first hide-out is closer to the top, the second about half an hour’s climb above his village Saver. Incidentally, Nadir and this boy are from the same village.”

“Excellent,” said the Colonel. “After clearing the second hide-out, bump this boy and make sure you get the body down after last light. We don’t want a hue and cry in his village. Simple as day to night,” said the Colonel. “But why the frown Anil? Something amiss?”

“No, I was just wondering, Sir, do we have to knock this boy out? I mean, he’s just a poor, confused, insignificant lad. Has an old sick mother at home. Frankly he hasn’t done enough damage to warrant such an early demise.”

“Really?” said the Colonel, a trifle annoyed now. “The entire effort hinges on this kill and now you tell me, you don’t want to do it?” The Colonel took a deep breath. Then composed, he smiled and looked at the young officer. “I know what’s going on in that head of yours, Anil. In our business, we can’t be too sensitive about death – quite a few good men are dead on either side. You have seen it in Sri Lanka. The innocents have to pay their price. It’s part of the game. And then, don’t forget this boy is cast in the same mould. Never surrendered a renegade like any of them. Have no qualms about this one.”

“Sri Lanka was different,” answered the Captain. “It was not my country. The fact Sir is that the boy is a victim of circumstances, like so many here.”

“Like you and me too Anil,” interjected the Colonel. “Puppets in a larger game, actors in a play. Aren’t we getting a mite philosophic now?”

“The point Sir,” persisted Anil, “this boy hasn’t done any harm, nor will he, if allowed to live. Myriad of eminent folks, in important positions have and are doing far more damage to this country then this boy has, or ever will. Surrendered hardcore militants with impunity are moving around with the Army. They need to be shot first.”

“Because for reasons Anil,” said the Colonel, “we can’t start sorting out the country at our level. This boy is expendable, serving our purpose, so he goes. You and I are no better. We are expendable too in the eyes of certain people. When the time comes, we too will be sacrificed for a cause that you may or may not agree with. Sadly, human life has no value in this lovely country of ours and unfortunately, we are men of action and after all only instruments of men of thought. The topic undoubtedly is double edged. What is right and what is wrong?”

“On one hand, the izzat of the unit, a little rest that you insure your fatigued men after the kill, on the other the justification of a harmless young militants death. Tell me Anil to cut out this un-soldierly debate, as a soldier, what punishment would you give for sedition, to one of your men?”

“The firing squad of course, Sir”

“There you are then,” said the Colonel smiling “and death it shall be. Now carry on and don’t involve too many of your boys, just a few should know. Remember he was shot while trying to escape.”

Anil went back to his company and summoned a tough looking Muslim Non Commissioned Officer (NCO) from Jammu. A solid professional soldier with very little time and sympathy for the so-called Jehadi’s who were ruining his state.

“Mushtaq,” he explained, “very quick from behind, a head shot make sure. No last wishes like the films. The boy shouldn’t know.”

“Don’t worry sahib, not the first one,” answered Mushtaq in a matter of fact manner.

They climbed at night, hitting the Lalpura ridge-line at first light. The Major ordered a break.

“Give the boy breakfast,” he ordered one of the men. “From here on” he told Rashid, “you lead to the hide.”

For the next four hours, they went around in circles, through the thick undergrowth.

“Where’s the hide Rashid,” inquired Anil.

“Jenab,” he stammered nervously, “it’s been nine months now. The complexion of the place has changed. This undergrowth wasn’t there. It’s under a large rock, next to a nala. I can’t seem to recognise any of the landmarks.”

“He’s been spinning yarns from the beginning sahib,” interjected Kuldeep. “Give me a little more time with him, he’ll remember everything,” he said, stepping forward menacingly.

“Lay off,” said Anil, as Rashid tucked himself in, anticipating a kick. “Doesn’t matter, we’ll try the next hide Rashid.”

They went down further. Five hundred feet above the village Rashid stopped.

“It’s on the left Sir,” he said turning to the officer, “under that gnarled tree.”

Sounds from the village below floated up to them in the tranquil evening. Smoke from the houses was spiralling up lazily in the still air. Tiny human figures could be seen making their way back home from the fields. The contented mooing of cattle and the faint laughter of children carried up to the waiting men. Lights appeared in a few houses as the villagers went about preparing for the night. For men who had been away from their families and home and had spent the past twenty four hours out under pressure in the wilderness, the sight below was a heady mixture to turn their mind to the comforts of civilisation. The effect of domestic peace so close yet so far was noticeable, as every member stood there with his thoughts, gazing longingly at the village below.

Rashid surveyed his village. He spotted his house and wondered what his mother was doing now. He passed the orchards he had played in, followed the path he had so often traversed till it turned at the big walnut tree and recognised Zaira’s house. Suddenly he was angry with her for getting him into this mess. Her smiling face came to his mind and he forgave her. For he realised, he loved her still. Profound nostalgia engulfed him. He turned to request the Major for one last meeting with his mother, but caught Kuldeep looking at him.

Major Anil Chaddha inhaled deeply the crisp mountain air. Rather peaceful for the job at hand he thought. He deployed the boys.

“Mushtaq, get your squad and let’s hit this hideout.”

They made their way cautiously through the bushes behind Rashid. It was a beautifully concealed hide. Rashid parted the foliage to reveal a twenty feet by ten feet hole in the ground. The tin roof had caved in and a pool of water had collected in one corner. The hideout had obviously been abandoned long back.

“This is the place jenab,” said Rashid, visibly relieved at having found it. “I told you Nadir must have moved out after I deserted.”

“Right, let’s go back,” said Anil, “Mushtaq check the area around and join the troop.”

“Yes Sir,” he said, exchanging a look, which needed no words and comes from having spent a lot of time together in tight spots.

“Come on, come on,” Anil told the rest of the men, “back to the column. Mushtaq don’t take too much time,” he shouted over his shoulder.

He joined the party deployed in the nala, raised the volume of his radio, so that the men could hear the transmission and waited.

Mushtaq stood behind Rashid and gently flicked the safety lever to rapid.

“How long did you stay here Rashid,” he asked.

“Two months.”

“I see. What’s that there, another hideout?” said Mushtaq pointing at a spot behind the boy.

“No motram,” said Rashid, turning to look in the direction.

The first shot missed his head shattering his collarbone. He spun violently and crashed on his back in the bushes, a surprised expression writ over his face. Briefly he had a glimpse of his executioner, as the second shot opened his skull like a flower, splattering his brains all over.

Unlike his father, Rashid Mogul died without any bitterness.

The loud report shattered the pregnant hush, followed by another. Men dived for cover. The Major went on the air immediately.

“Two zero for two one, two zero for two one, where’s the fire from?”

“Mine, mine,” said an excited breathless voice, loud and clear. There was a brief pause and then Mushtaq’s voice crackled again.

“The boy was trying to run, I shot him dead.”

“Roger,” said Anil, “I am sending a few boys to help you carry his body down.”

In the valley below, the muffled sound of gunfire was heard. People looked up at the dark form of the mountain wondering then carried on with their work. After all, in the Lolab, it wasn’t the first time they had heard that sound.

The old woman too looked up then smiled thinking of Rashid far away in Srinagar. She lit the wicker lamp and looked out towards the big walnut trees. Then for some strange reason, she came out on the veranda with the lamp. “Rashid, Rashid, my son” she called out in the darkness. Briefly, she waited for a reply she didn’t expect, and then went back. She sat down alone for her frugal meal, watching the flickering flame take grotesque shapes on the barren wall and thinking of her only son. Then suddenly the flame went out plunging her in darkness and without realising, the old woman had tears in her eyes.

Anil looked at the body and strangely it struck him, how similar they all looked in death. Violent death in hostile surroundings probably takes away the solemnity of a dead body. Or maybe he had become callus where other’s suffering was concerned, indifferent to death, even to its more ugly aspects. Already the features on the boy’s face were getting blotched, as if melting into his face. It was just another face. The time when a body had an emotional effect was long since gone. He had seen too many of them. It was the living he felt sorry for. The fact of death was all that mattered.

It was dark by the time they arrived at the village. The body was handed over to the village headman.

Major Anil Chaddha looked at the body for the last time. Then pulling out a few hundred-rupee notes from his pocket, he gave them to the headman.

“The money belonged to the boy, give it to his mother.” Then turning he walked down the path, under the big walnut trees.

Information had already been passed to higher formation and the situation report initiated, even before the party arrived back at base. The reply was equally fast.

“Shabash Anil,” said the Colonel, “the Brigade Commander is pleased. Give me the names of the boys, who have performed well. Read the situation report initiated by us and stick to it.”

Raided ANE hide in GR 583862 (.) killed one PTM/ Rashid Mogul (.)

Recovered AK-47——–1,

AMN ———120 rounds,

Grenades —–04

Misc. Equipment. ——- Destroyed in Situ.

Major Anil Chaddha came back to his room a tired man.

“No tea Balwant,” he told his helper, “get me a large rum instead and no paani. Today, I drink to get drunk.”

And by the time the first drink had settled, warming his innards, it disturbed him that the death of the young boy with the large melancholy eyes was already receding into the far recess of his memory. He felt sorry for the boy. Happiness in his case had been an occasional episode in a general drama of misfortune. And just before sleep overtook him, he remembered a parable he had read as a young man.

There was once a merchant in Baghdad. His servant came to him one day, ashen faced trembling and said, “I was in the market place master, when some one jostled me and as I turned, I saw it was Death. It had an intimidating expression that scared me. So give me a horse Master, for I want to get away from here. I am going to ride away to Samara.”

So the merchant gave him a horse and the servant rode away. Then the merchant went down to the market place and seeing Death accosted it, demanding why it had scared his servant with that intimidating expression.

“It was not an intimidating expression,” replied Death, “but a start of surprise to see him here. For I had an appointment with him in Samara.”